Jeff Gothelf, tell me about yourself. Who are you?

My name is Jeff Gothelf and I am a designer, product manager, and entrepreneur. Currently, I operate as an author, speaker, trainer, and coach, primarily collaborating with mid-sized and large companies. My expertise lies in bridging the gap between lean, agile design thinking, customer-centricity, and product management. Lately, I’ve been dedicating a significant amount of time to focusing on product management and implementing objectives and key results.

And tell me more about your interest in Objectives and Key Results, OKRs?

Yeah, I’m really passionate about OKRs. It’s been a focus for me throughout my career. I started as a designer and then became a design leader, aiming to blend design with Agile software development. But I kept facing the same challenge: setting effective goals and incentives for teams. Over the past 15 years, I’ve been working on this. I believe that when OKRs are done well, they lead to organizational agility, customer focus, teamwork, and creating excellent products.

Before we delve into that, could you please explain OKRs for our audience?

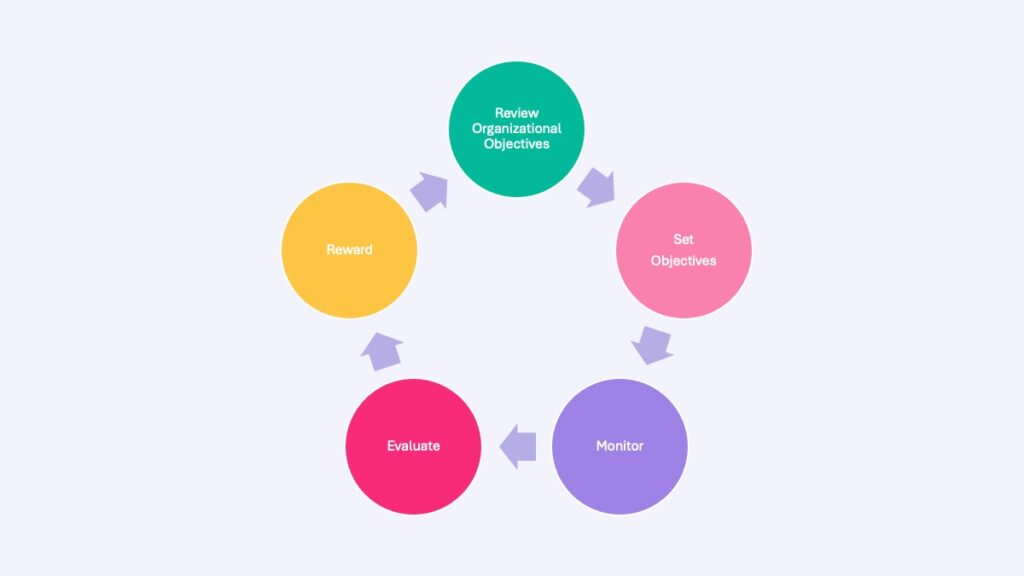

OKRs, or Objectives and Key Results, are a goal-setting framework designed for teams. It emphasizes setting qualitative objectives to align the team’s focus and direction. The objectives answer the question: Why are we doing this work? Additionally, OKRs include quantifiable key results that indicate whether we’ve achieved our objectives.

We emphasize a fundamental difference in how we define OKRs. We believe that key results must measure outcomes, particularly changes in human behavior. This means that our focus is on the people we serve—our customers or consumers. When we observe meaningful changes in their behavior, we know that we’ve successfully met their goals and our own objectives. That’s how we define OKRs.

You mentioned your background in design. It’s often said that setting key results for designers is challenging. What are your thoughts on this?

Well, I don’t believe we should set goals specifically for individual disciplines. Instead, the focus should be on building cross-functional teams—combining product design, engineering, and other areas—to tackle customer and business problems collectively. In this approach, OKRs are assigned to the entire team, so they succeed or fail together. It’s not about one person doing their job while others don’t. Everyone shares the OKR.

Now, while you can have discipline-specific OKRs, they should center around enhancing the discipline itself rather than the product. For example, you could set an objective and key result to improve the design or engineering department internally. This focuses on optimizing team structure, processes, recruitment, and retention. However, when it comes to product-centric goals, the OKRs should involve everyone contributing to product development.

Some companies I’ve spoken to implement OKRs on an individual level. What are your thoughts on that approach?

I believe it’s wrong. When OKRs are set for individuals, the focus shifts to changing individual behavior. This can make it challenging to measure progress accurately, and individuals may be tempted to manipulate the system to meet their goals, especially if bonuses or promotions are tied to performance. Let’s take an example: a software engineer sets a goal to become a ’10X engineer’ and completes programming classes, reads books, and takes online courses. But does completing these tasks truly make them a ’10X’ engineer? It’s unclear. OKRs are designed for team-based goal setting.

However, this raises the question: what should be the performance management criteria for individuals if OKRs are team-based? Traditionally, success is measured by production and delivery—did you create the product or not? But rarely do we measure if people actually use the product.

To address this, we need to detach rewards and incentives from OKRs to prevent gaming the system. Additionally, we should focus on indicators like decision-making, customer understanding, knowledge sharing, and collaboration to gauge success. Defining exact metrics for these can be challenging, and it’s one reason why OKRs often fail. Implementing OKRs isn’t just about the concept; it’s about navigating the complexities of performance management.

In a team-focused goal-setting setup, how do we judge individual performance?

Just to clarify, I’m not an HR expert. In my experience, success in teams I’ve been part of, led, or advised has been mainly measured by output and delivery. It’s straightforward to gauge: did you complete the task or not? However, rarely are rewards tied to whether people actually use what’s produced. So, what should we prioritize? First, we should disconnect rewards from hours worked, as people tend to game the system otherwise. Remember the Wells Fargo scandal? Secondly, we should focus on how decisions are made, the effort towards understanding the customer, and the ability to share knowledge and collaborate effectively. Pinning down exact metrics for these can be tricky, and it’s one reason why OKRs often struggle. Integrating performance management into such frameworks is tough and often overlooked.

I’ve talked to companies and leaders who’ve stopped using OKRs after repeated failures. They initially adopted it years ago but found it too complex, especially when transitioning from yearly to quarterly cycles. What advice would you offer these companies? How can they succeed with OKRs?

Yeah, so here’s the deal – we’ve actually put together a comprehensive book addressing all these concerns called ‘Who Does What by How Much,’ slated for release April 2024. Now, the crux of the matter is this: implementing this approach requires solid top-down support. It’s essential to understand there will be some initial overhead and a learning curve, and we’ll need to adjust course along the way. We might initially overload calendars with meetings or, conversely, not schedule enough. We might even measure the wrong things or overlook important metrics. But that’s where dedication and support come in. We need leadership backing and the flexibility to experiment and learn from mistakes, just as we do with our products and services. If we’re willing to adapt and iterate, the benefits will far outweigh the challenges, in my opinion.

Could you provide some general advice? For instance, how many objectives and key results should a company and team aim for? What’s an ideal cycle structure? Can you share specific practices that have proven effective?

In an ideal scenario, each business unit should have one objective and up to three key results. More than that, and you risk diluting focus. The objective typically spans a year, while key results shift quarterly, though not always. Teams should meet weekly for informal check-ins and communicate regularly with executives via email or Slack. Monthly progress reports and quarterly OKR reviews with executives help ensure alignment and course correction when needed.

A crucial point to remember is that neither the objective nor the key results should dictate a specific solution. Instead, teams should focus on discovering the best approach through methods like product discovery, design thinking, lean startup, and Lean UX. Encouraging and supporting this exploration is vital for achieving desired outcomes.

What are your thoughts on incorporating ‘business as usual’ tasks into OKRs? Would you suggest that they should not be included in the OKR framework?

Could it be complicated or confusing for an employee who spends at least 70% of their day on ‘bread and butter’ revenue-generating tasks, crucial for customer satisfaction? How should we balance transformational work with business as usual?

Firstly, OKRs prioritize business goals for the quarter, with most teams focusing accordingly. Transformational work, however, requires separate ownership and internal-facing OKRs geared towards organizational change.

For business as usual tasks, existing metrics like system uptime, DevOps, call center, and security are essential. The dilemma lies in whether to leave these departments to optimize these metrics independently or to align their efforts with customer service goals.

Sales teams, for instance, may resist OKRs, prioritizing hitting their numbers over collaboration. Conversely, stability and reliability teams may endlessly optimize system uptime, prompting the question of when enough is enough. Should we tie business unit metrics to customer behavior metrics? Yes, and it’s a conversation worth continuing.

Yeah, it’s tough. Objectives should resonate with everyone in the organization, so we need broader company-level goals to include and excite everyone.

Yeah, exactly. I mean, think about it. If you’re a site stability engineer, is adding another nine after the decimal point really what gets you out of bed in the morning? I have a client who’s obsessed with this—4 nines, 5 nines. But do I really want to aim for 6 nines? Is that why I do what I do? Honestly, I’m not sure. But let’s shift gears and talk a bit about employee engagement, because not everyone finds excitement in transformational steps.

How can you excite everyone in the company if you implement OKRs, is it impossible?

It’s absolutely possible, and it starts with executives modeling the behavior they want to see in their teams. Traditionally, executives dictate the direction with unwavering confidence, but what we really need is a willingness to adapt based on new information. Executives should lead by example, demonstrating that it’s okay to change course when evidence suggests it’s necessary. By admitting when they’re wrong and pivoting accordingly, leaders foster a culture of continuous improvement and innovation. When teams see this openness and agility from their leaders, they’re more inclined to embrace product and customer discovery, leading to better products and greater care for customer needs.

Do you have anything to add about OKRs?

Let’s face it, OKRs, like many new organizational ideas, often come with baggage and mismanagement. But if we strip it down to its essence – a qualitative goal and measures of human behavior to gauge success – it’s quite straightforward. Starting small with one or two teams, figuring it out, and then scaling up is a smart way to mitigate the risks associated with major change.